-

Minimal Handling

Stop touching the patient. Often enough in paediatrics, more is not better. This is of key importance in the younger age group. The more lights/monitors and hands on assessment – the more distressing to the child. The more distress – the greater the effort of breathing becomes. Most children with wheeze are best assessed and managed in a parent’s arms, in a dimly lit room with soft music or tv playing. Interventions should be grouped and minimised. Saturation probes placed under socks and connected intermittently to a monitor prevent the child being disturbed and the constant alarming of machines. Observation of RR and work of breathing can be recorded from a distance without disturbing the patient.

-

Salbutamol – yes or no?

Salbutamol – the panacea of wheeze! Except we know it is ineffective in children with bronchiolitis. So how do we guage who it is effective in and how much is too much? While salbutamol is an excellent bronchodilator it is not without side effects. Lung development is not complete until approximately age 7 – many young children simply do not have sufficient smooth muscle to respond to bronchodilators. Salbutamol comes with significant risk of side effects the most important of which is salbutamol toxicity:

Salbutamol causes:

- tachycardia,

- tachypnoea

- Hypokalaemia

- tremor

- ventilation/perfusion mismatch (sats appear lower on therapy)

- Lactic Acidosis!!

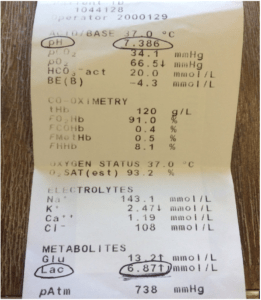

This is a blood gas of an 18 monther given 10mg of inhaled salbutamol.

The patient had a profound symptomatic lactic acidosis – pale, sweaty, tachycardic, tachypnoeic, desaturated, vomiting.

This symptomatology can have a marked impact on inappropriate escalation of treatment in wheezy kids where time may be a better differentiator. Young children who improve after an initial “burst” therapy but still have some residual wheeze and work of breathing may not yet be entirely salbutamol responsive. Pushing their salbutamol intake up and up will rapidly lead to toxicity and a deterioration in the patient’s clinical state. Time and treatment as for bronchiolitis is almost certainly a safer plan.

-

Steroids – yes or no?

There has always been some uncertainty about the benefit of prednisolone for viral wheeze in pre-school children. In 2009, a study by Panickar et al[1] found that there was no positive effect in giving steroids to pre-school children with wheeze. They included children aged 10 months to 2yrs which was a source of controversy given the potential overlap with the bronchiolitis cohort.

Foster et al[2] sought to revisit this issue by undertaking an RCT comparing steroids with placebo in children aged 2-6yrs. They excluded severely ill children and those with recent steroid use. Although they found some difference in children on the milder end of the spectrum in a reduced length of stay, there was no statistical difference in number of representations or PICU admissions of either group.

The response to this has been varied. Of note, the Australian Asthma Handbook[3] continues to recommend the use of oral steroids in only the group requiring hospitalization for severe illness. Parent initiated steroids are also not recommended as they do not alter outcomes.

My practice is to use oral prednisolone only in the group I am admitting to a ward bed due to severe disease. In the older cohort commencing primary school I start to adjust prescribing aiming at those with a greater burden of atopic disease who are more likely to suffer long term asthma. In those patients I expect to go home within 12 hrs, I do not prescribe steroids. I encourage GP’s not to prescribe pre-hospital to try to limit an individual child’s lifetime steroid exposure in an effort to limit potential long term effects.

-

High flow O2

Is this the new panacea in wheezy children?

How does it work?

2L/kg nasal prong O2

Provides low level pressure support – prevents supraglottic collapse and decreases nasopharyngeal resistance.

Advantages:

- Low levels of PEEP may contribute to alveolar recruitment, improved compliance and decreased work of breathing

- Better tolerated than NCPAP

- Humidification – preserves nasal mucosa and more comfortable

- Nasopharyngeal dead space decreases CO2 rebreathing and provides an oxygen reservoir

Disadvantages:

- PEEP drops when the patient’s mouth is open (insert dummy to minimise)

- PEEP is variable and not measurable

- More costly than low flow

Complications:

- Local trauma, discomfort and pressure areas

- Gastric distension

- Blocked cannulae due to secretions[4]

EVIDENCE

Remains controversial

- Failure of HFNC might cause delayed intubation and worse clinical outcomes in patients with respiratory failure[5]

- The FLORALI study found no difference in intubation rates in patients with acute hypoxaemic respiratory failure treated with either high-flow nasal oxygen, Hudson mask oxygen, or NIV. There was a significant difference in favour of high-flow nasal oxygen in 90 day mortality[6]

- We are waiting patiently for the outcome of PARIS 1 trial to guide us further with this specific patient cohort.[7]

-

Blood gas – yes or no?

This one’s easiest. It’s an almost universal no. Assessment of oxygen saturations are accurate. Combined with concentrated assessment of work of breathing, conscious state and general demeanour and frequent reassessment we have effective methods of determining those patients at risk of hypercarbic respiratory failure. Venous blood gases may be useful only to assess reasons why a child on escalating treatment is failing to improve.

Join us at EMCORE Hong Kong for the next instalment – 5 steps to avoid intubating a child….

References

[1] Panickar J et al. Oral prednisolone for preschool children with acute virus-induced wheezing. New England Journal of Medicine. 2009 Jan 22;360(4):329-38.

[2] Foster S J et al. Oral prednisolone in preschool children with virus-associated wheeze: a prospective, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. The Lancet Respiratory Medicine Jan 2018, 6 (2): 97-106.

[3] http://www.asthmahandbook.org.au/management/children/0-5-years/acute-wheeze

[4]https://www.rch.org.au/picu/about_us/High_Flow_Nasal_Prong_HFNP_oxygen_guideline/

[5] Kang BJ et al. Failure of high-flow nasal cannula therapy may delay intubation and increase mortality. Intensive Care Med. 2015 Apr;41(4):623-32.

[6] Frat JP et al. High-flow oxygen through nasal cannula in acute hypoxemic respiratory failure. N Engl J Med. 2015 Jun 4;372(23):2185-96.

[7] Franklin, D et al. Early high flow nasal cannula therapy in bronchiolitis, a prospective randomised control trial (protocol): a Paediatric Acute Respiratory Intervention Study (PARIS). BMC Pediatrics, 2015. 15: 183.

Dr Claire Wilkin Marshall

Dr Claire Wilkin Marshall

Paediatric Emergency Physician