How to Perform Pericardiocentesis

Pericardiocentesis is used to treat symptomatic pericardial effusions and cardiac tamponade. It was first described in the 1650’s and since the introduction of the subxiphoid approach in 1911, has been used very successfully, with significant reduction in morbidity and mortality. The use of echocardiography and other guidance techniques have reduced the risks even further.

A CASE WE HAD RECENTLY

An 80 yo male presents with 9/10 central chest pressure. It awoke him in the middle of the night. After several hours he called the ambulance who treated the patient with GTN spray and the pain improved markedly.

PMHx

Pacemaker inserted 2 days ago

Thyroidectomy

Type II Diabetes

Left Inguinal Hernia Repair

TURP 2009

In the emergency department the vitals were:

T 36.9, HR 60, BP 145/75, SaO2 99% on room air, Resp Rate 16.

Patient ECHO

The patient continued to have chest pain. He was treated with further sublingual GTN, after which he dropped his blood pressure and required a total of 500mL of Normal Saline to return it to 115mmHg systolic. The blood pressure continued to fall reaching 70mmHg systolic and a Metaraminol Infusion was commenced.

A bedside ECHO revealed a pericardial effusion, which was felt to be responsible for the ongoing hypotension.

This tied in well with the drop in blood pressure, with the use of GTN, given that pericardial effusions usually cause a right ventricular collapse.

The decision was made to perform a pericardiocentesis.

Indications for Pericardiocentesis

- A pericardial effusion causing haemodynamic compromise

- Symptomatic large effusions not responding to medical treatment.

- Smaller effusions that are bacterial, tuberculous or neoplastic in origin

Contraindications to Pericardiocentesis

- There are no real absolute contraindications when the patient is decompensating and in shock

- Relative contraindications include coagulopathy, thrombocytopaenia and anticoagulant therapy

Techniques Used

There are several techniques available including CT guided and Fluoroscopy guided, however for use in the emergency department the safest and simplest approach is echocardiography-guided.

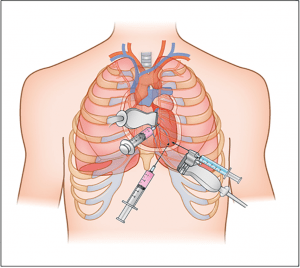

Different Pericardiocentesis Approaches and Risks

Source: European Society of Cardiology Journals. E-Journal of Cardiology Practice. Volume 15

There are 3 anatomical approaches to needle insertion:

- Parasternal: Catheter insertion is at the left 5th intercostal space adjacent(<<1cm) to the sternal margin. This approach carries a risk of pneumothorax, and damage to the internal thoracic vessels.

- Apical:Catheter insertion in the 5-7th intercostal space, 1-2 cm lateral to the apex beat. There is an increased risk of pneumothorax and of ventricular puncture.

- Subxiphoid(also called paraxiphoid):The catheter is inserted between the xiphisternum and the left costal margin, directed towards the left shoulder. There is a lower risk of pneumothorax, however there is a risk of entering the peritoneal cavity, of puncturing the right atrium and puncturing the left lobe of the liver.

How to Perform a Pericardiocentesis

The video below goes through the procedure performed in this case. The following steps are involved:

- Explain to the patient what you are going to so.

- Place patient in semi-reclining position with head up about 20 degrees.

- Aseptic Technique, use a pericardiocentesis tray.

- Paraxiphoid approach is used and the needle is directed towards the opposite shoulder at about 40 degrees to the skin.

- The catheter insertion is guided by echocardiography.

- When the pericardial space is entered and there is flashback of fluid into the syringe, ‘agitated’ normal saline is injected. This allows confirmation that you are in the right space.

- Feed the guidewire as per Seldinger technique and then dilate with the introducer and feed the pigtail catheter over this.

- Aspirate blood from the cavity and then allow drainage etc.

A few things to remember:

Pericardial fluid does not clot, but blood does.

The volume of fluid is calculated by the size of the effusion on echo.

- Normally the pericardial sac can contain up to 50mL of fluid.

- 5-10 mm: 100-250 mL

- 10-20 mm: 250-500 mL

- >20 mm: >500 mL

Watch the 4 minute video below

BACK TO THE CASE

A total of 260mL of fluid was removed and a pigtail catheter was inserted. The Metaraminol infusion was stopped whilst the aspiration was under way. On completion, the blood pressure rose naturally to a normal level.

This is not a procedure we take lightly. However in a situation like this, it was necessary and showing you the way it was done, I think you will agree, it is straightforward, thanks to echocardiography.