You’ve just seen a patient with sudden onset of headache. They have presented within 6 hours and your super-sliced scanner spits out a normal CT brain. Are you done? You apply shared decision making with your patient and decide against a lumbar puncture. Are you done? Beware the mimics; amongst them cerebral venous thrombosis and carotid artery dissection.

Cerebral venous thrombosis is a rare diagnosis, but a very important diagnosis to make. It occurs in the younger population and has an insidious onset.

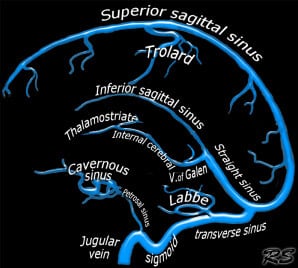

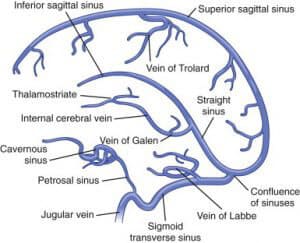

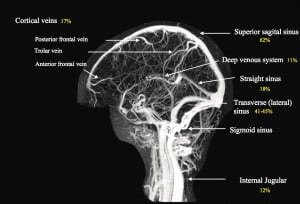

A Little Anatomy

Cerebral veins include the dural sinus and cerebral veins. They include the transverse, sigmoid and cavernous sinus, the superior sagittal sinus, inferior sagittal sinus and the straight sinus.

CLINICAL FEATURES

Cerebral Venous Thrombosis(CVT) represents approximately 1% of strokes(1), and tends to occur in the younger population ie., those less than 50 years of age(2). A small percentage of these patients will present with thunderclap headache.

Symptoms may depend on the underlying pathology and relate to(3):

- Raised Intracranial Pressure secondary to impaired venous drainage

- HEADACHE: This is the most common presenting symptom

- The headache is usually diffuse in nature and progresses over a period of days or weeks.

- There appears to be no association between the location of the headache and the site of venous thrombosis.

- In up to 5% of cases it can present as thunderclap-like headache(4, 19)

- It can present as a single finding with no neurology in up to 25% of cases(4)

- Look for papilloedema and sixth cranial nerve palsy, presenting as diplopia.

- HEADACHE: This is the most common presenting symptom

- Focal brain injury caused by ischaemia/infarction or haemorrhage

- APHASIA

- HEMIPARESIS

Symptoms may also depend on thrombus location

- Superior Sagittal Sinus

- Most commonly involved sinus

- Headache and papilloedema

- Can lead to motor deficits.

- Lateral Sinus

- Headache

- Hemoanopia, contralateral weakness and aphasia

- Deep Cerebral Venous( internal cerebral vein, vein of Galen and straight sinus)

- Result in rapid deterioration, secondary to thalamic or basal ganglion infarction.

How to Differentiate CVT from Cerebrovascular Disease

This can be very difficult to do, however there are some specific characteristics of CVT(4)

- Seizures(focal or generalised) are frequent, occurring in up to 40% of population

- The patient may have bilateral signs i.e. bilateral motor signs.

- The patient may have a progressive depressed level of consciousness, with no focal signs if there is bilateral thalamic involvement.

- Signs progress slowly, with delays from symptom onset to diagnosis being on average about 7 days(5)

Presentations that can distract us from diagnosing CVT

- A percentage of patients with CVT present with an intracranial Haemorrhage(6) This varies in the literature from 5% in a younger population (8), to as high as 30% in other studies(9). Up to 0.8% of patient with CVT will have a subarachnoid haemorrhage.

- When SAH does occur it is not in the Circle of Willis as would be expected, but outside it(5)i.e.., there is a different pattern of bleeding in these conditions

- Headache as the only symptom occurs in 25% of cases(4)

- Headache and papilloedema/sixth cranial nerve palsy

- All patients with evidence of intracranial hypertension need magnetic resonance venography as the presence of the disease in this group has been found to be as high as 10%(7).

- Presentation with confusion and no focal signs, in cases of bilateral thalamic involvement.

- MRI is the imaging of choice here.

What are the Risk Factors?

Think of this condition in patients with pro-thrombotic states.

- Antithrombin III Deficiency

- Protein C or S Deficiency

- Antiphospholipid and Anticardiolipin Antibodies

- Resistance to Active Protein C

- Factor V Leiden gene mutation

- Hyperhomocysteinemia

- Pregnancy and Postpartum period

- Prothombotic states during pregnancy and for about 6 weeks postpartum(10)

- 2% of pregnancy related strokes are caused by CVT(11)

- Most occur in the third trimester or postpartum

- Oral Contraceptive

- Cancer

Investigations

Laboratory

- Blood tests: FBC, EUC, LFT, ESR, PT, APTT

- These may assist in determining a hyper coagulable state.

- D-dimer: This may assist in ruling out the diagnosis in a similar way as it is used in pulmonary embolism diagnosis ie., a normal D-dimer, with a low pre-test probability. Some studies show a negative predictive value of up to 99.6%(12), whilst others show a degree of false negatives(13). It appears that if there is a low pretest probability and normal D-dimer, the risks are small, however there is a higher false negative rate, in those with headache as the only symptom, and in those where the process has been ongoing for several days.

- Lumbar Puncture: There are no specific findings in lumbar puncture, to assist with the diagnosis:

- High opening pressures occur in >80% of patients with CVT(5)

- There may also be elevated cell counts and protein readings.

- Non-Invasive Imaging

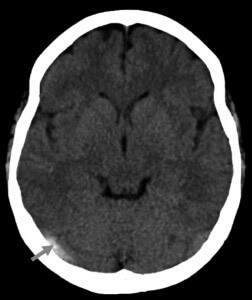

- CT- non-contrast: it is abnormal in only about 30% of cases of CVT(14).

The main abnormality to be seen is a hyperdensity, usually in the region of the transverse sinus(15). This is sometimes called the ‘cord sign’, shown above. A false positive cord sign may also be seen in the setting of generalised cerebral oedema

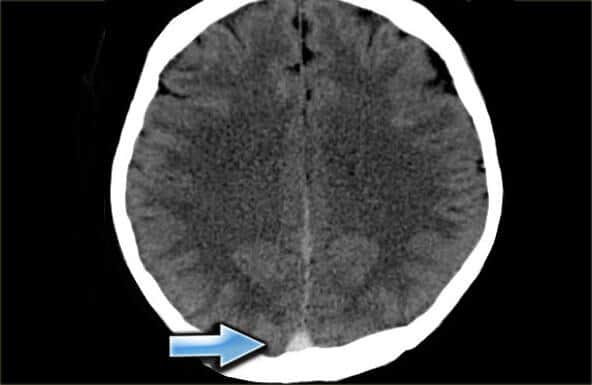

From The Radiology assistant- Above the dense triangle sign.

If the thrombosis is in the posterior part of the superior sagittal sinus, the dense triangle or filled delta sign may occur; shown above.

A CT Brain with contrast may demonstrate the empty delta sign, which indicates thrombus at the posterior part of the superior sagittal sinus. See below:

Case courtesy of A.Prof Frank Gaillard

CT with contrast or a CT venogram(CTV), will give more information than a non-contrast CT alone(15). CTV is as good as MRV in giving a diagnosis(16). MRI is overall more sensitive than CT in diagnosing CVT(15).

- Invasive Imaging

- Cerebral Angiography, will show a filling defect.

- Direct Cerebral Venography demonstrates an occluding thrombus and is performed by direct injection into a dural sinus.

TREATMENT

This is a difficult condition to treat.

- Anticoagulation: The trials here are small. However a review of the two major trials(17) shows a benefit of anticoagulation, with heparin or low molecular weight heparin.

- Care must be taken in those patients that may have had a bleed secondary to CVT

- We are unsure of the role of aspirin, as no studies have been done.

- Fibrinolysis: Use them if the patient continues to clinically deteriorate despite anticoagulation.

- Catheter Thrombolysis: There may be some benefit in those with severe CVT(18)

- Catheter Thrombectomy: This may be considered when fibrinolysis has failed.

Conclusion

Cerebral venous thrombosis can be a difficult diagnosis to make. It’s a matter of thinking of it.

It has an insidious nature and that may give it away. The progressive headache, bilateral neurology, signs of raised intracranial pressure all assist. In those with a diagnosis of stroke, it may still be there.

In those patients with a thunderclap headache and a normal CT and even normal lumbar puncture, ask the question, especially in those patients with prothombotic states; “Could it be Cerebral Venous Thrombosis?”.

Its easy to say; “What’s the point?” It’s rare, it occurs in 5 in every million of the population annually and in about 1% of strokes(14). “I’ll probably never see it in my lifetime”. It will occur in someones lifetime. It occurs in the younger patients and may respond to treatment. We need to be aware. Isn’t that what we do?

Peter Kas

References

- Stam J. Thrombosis of the cerebral veins and sinuses. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:1791–1798.

- Canha ̃o P, Ferro JM, Lindgren AG, Bousser MG, Stam J, Barinagarre- menteria F; ISCVT Investigators. Causes and predictors of death in cerebral venous thrombosis. Stroke. 2005;36:1720–1725.

- Saposnik G et al. Diagnosis and Management of Cerebral Venous Thrombosis. Stroke. 2011;42:1158-1192

- Cumurciuc R, Crassard I, Sarov M, Valade D, Bousser MG. Headache as the only neurological sign of cerebral venous thrombosis: a series of 17 cases. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2005;76:1084–1087

-

Ferro JM, Canha ̃o P, Stam J, Bousser MG, Barinagarrementeria F; ISCVT Investigators. Prognosis of cerebral vein and dural sinus throm- bosis: results of the International Study on Cerebral Vein and Dural Sinus Thrombosis (ISCVT). Stroke. 2004;35:664–670.

-

Girot M, Ferro JM, Canha ̃o P, Stam J, Bousser MG, Barinagarre- menteria F, Leys D; ISCVT Investigators. Predictors of outcome in patients with cerebral venous thrombosis and intracerebral hemorrhage. Stroke. 2007;38:337–342.

-

Lin A, Foroozan R, Danesh-Meyer HV, De Salvo G, Savino PJ, Sergott RC. Occurrence of cerebral venous sinus thrombosis in patients with presumed idiopathic intracranial hypertension. Ophthalmology. 2006; 113:2281–2284.

-

Janghorbani M, Zare M, Saadatnia M, Mousavi SA, Mojarrad M, Asgari E. Cerebral vein and dural sinus thrombosis in adults in Isfahan, Iran: frequency and seasonal variation. Acta Neurol Scand. 2008;117: 117–121.

-

Wasay M, Bakshi R, Bobustuc G, Kojan S, Sheikh Z, Dai A, Cheema Z. Cerebral venous thrombosis: analysis of a multicenter cohort from the United States. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2008;17:49–54.

-

Davie CA, O’Brien P. Stroke and pregnancy. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2008;79:240–245.

-

James AH, Bushnell CD, Jamison MG, Myers ER. Incidence and risk factors for stroke in pregnancy and the puerperium. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;106:509 –516.

-

Kosinski CM, Mull M, Schwarz M, Koch B, Biniek R, Schla ̈fer J, Milkereit E, Willmes K, Schiefer J. Do normal D-dimer levels reliably exclude cerebral sinus thrombosis? Stroke. 2004;35:2820–2825.

-

Crassard I, Soria C, Tzourio C, Woimant F, Drouet L, Ducros A, Bousser MG. A negative D-dimer assay does not rule out cerebral venous thrombosis: a series of seventy-three patients. Stroke. 2005;36: 1716 –1719.

-

Bousser MG, Ferro JM. Cerebral venous thrombosis: an update. Lancet Neurol. 2007;6:162–170.

-

Leach JL, Fortuna RB, Jones BV, Gaskill-Shipley MF. Imaging of cerebral venous thrombosis: current techniques, spectrum of findings, and diagnostic pitfalls. Radiographics. 2006;26(suppl 1):S19 –S41.

-

Linn J, Ertl-Wagner B, Seelos KC, Strupp M, Reiser M, Bru ̈ckmann H, Bru ̈ning R. Diagnostic value of multidetector-row CT angiography in the evaluation of thrombosis of the cerebral venous sinuses. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2007;28:946 –952.

-

Stam J, De Bruijn SF, DeVeber G. Anticoagulation for cerebral sinus thrombosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2002;(4):CD002005.

-

Canha ̃o P, Falca ̃o F, Ferro JM. Thrombolytics for cerebral sinus throm- bosis: a systematic review. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2003;15:159–166.

- Wasay M, Kojan S, Dai AI, Bobustuc G, Sheikh Z. Headache in Cerebral Venous Thrombosis: incidence, pattern and location in 200 consecutive patients. J Headache Pain.2010 Apr. 11(2):137-9