Patients presenting with syncope to the Emergency Department can pose a significant diagnostic challenge. The two main reasons for this are:

- Syncope is a symptom, not a diagnosis. We need to search for the underlying cause.

- Adverse events can occur, when none are obvious or predictable during our Emergency Department evaluation. We know that the rate of adverse events in the first thirty days may approach 25%.

The Canadian Syncope Risk Score (Thiruganasambandamoorthy, V et al, CMAJ, September 6, 2016, 188(12)) has been published and may prove to be the next score we use, once it’s validated.

Definition of Syncope

Three things must occur for an event to be called syncope.

- There must be a transient, short-lived loss of consciousness

- There must be loss of tone, usually postural and

- There must be a rapid return to baseline.

These are the important basics. Although we speak of loss of consciousness, we often include pre-syncope with syncope to minimise any misses. There is usually a loss of postural tone ie, the patient becomes limp. If standing, they will collapse. Syncope may occur whilst sitting or even lying and this is a red flag. The return to baseline is a very important part of this definition. Return to baseline must occur, ie the patient must have no deficit. We usually expect this to occur within 5 minutes, although it usually occurs much earlier than that. Abnormal conscious state past this first five minutes may indicate another cause such as seizure.

Prediction Rules

There have been many different syncope prediction rules proposed in the past.

- The San Francisco Syncope Rule (Annals of Emerg Med. 2004; 43;2: 224-232) is perhaps the most famous. It aimed to predict seven day adverse outcomes and was sensitive but not very specific. It did not pass the validation test. It included markers such as:

- abnormal ECG,

- shortness of breath,

- systolic BP < 90mmHg,

- decreased haematocrit and

- congestive cardiac failure.

- The ROSE Score( Risk Stratification of Syncope in the Emergency Department) (J Am Coll Cardiol 2010;55:713-721), looked at one month adverse events and all cause death. It showed a sensitivity of 87% and specificity of 65%, but again did not pass the validation test. It included the following markers for admission:

- BNP

- Bradycardia

- Fecal Occult blood on rectal examination

- Anaemia

- Chest pain associated with syncope

- ECG with Q waves

- Oxygen saturations < 95%

- The Boston Syncope Rules (J Emerg Med. 2007 Oct; 33(3): 233–239) looked at 25 predictors of thirty day adverse outcomes, based on ACEP policy documents. These predictors included:

- Signs and symptoms of acute coronary syndrome

- Abnormal ECG

- Cardiac History

- Family History of sudden death

- Abnormal vital signs

- Valvular disease …. and others

- The OESIL Risk Score (Eur Heart J. 2003 May;24(9):811-9) looked at one year mortality and had 9 risk factors. The more risk factors the higher the risk of an adverse outcome. These factors included:

- Age > 65

- Males

- Hypertension

- Cardiovascular history

- Diabetes

- Previous syncope

- Syncope and no prodrome

- Syncope related traumatic injuries

- Abnormal ECG

- The STePS Study(Short Term Prognosis of Syncope) (J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008 Jan 22;51(3):276-83) looked at 10 day and one year adverse events and included such factors as:

- Abnormal ECG

- No Prodrome

- Male gender

- Age > 65

- Structural Heart disease

- Ventricular arrhythmias

There were several more. What they all appear to have in common is that patients with:

- Cardiac History

- Abnormal Vital Signs

- Syncope more likely due to cardiac causes than vasovagal causes ie., no prodrome

- Abnormal ECG

…………..have potentially worst outcomes. This is sensible medicine.

These rules lack the sensitivity plus specificity to be used and accepted as standard of care.

A New Rule

The Canadian Syncope Risk Score has been proposed as a clinical decision rule that can be used to identify adults with a 30 day risk of serious adverse event, which includes death, arrhythmia, myocardial infarction, aortic dissection,pulmany embolism and subarachnoid haemorrhage.

This was a Prospective Observational Study of adults who presented within 24 hours of an event.

Total number of patients included in the study was 4030.

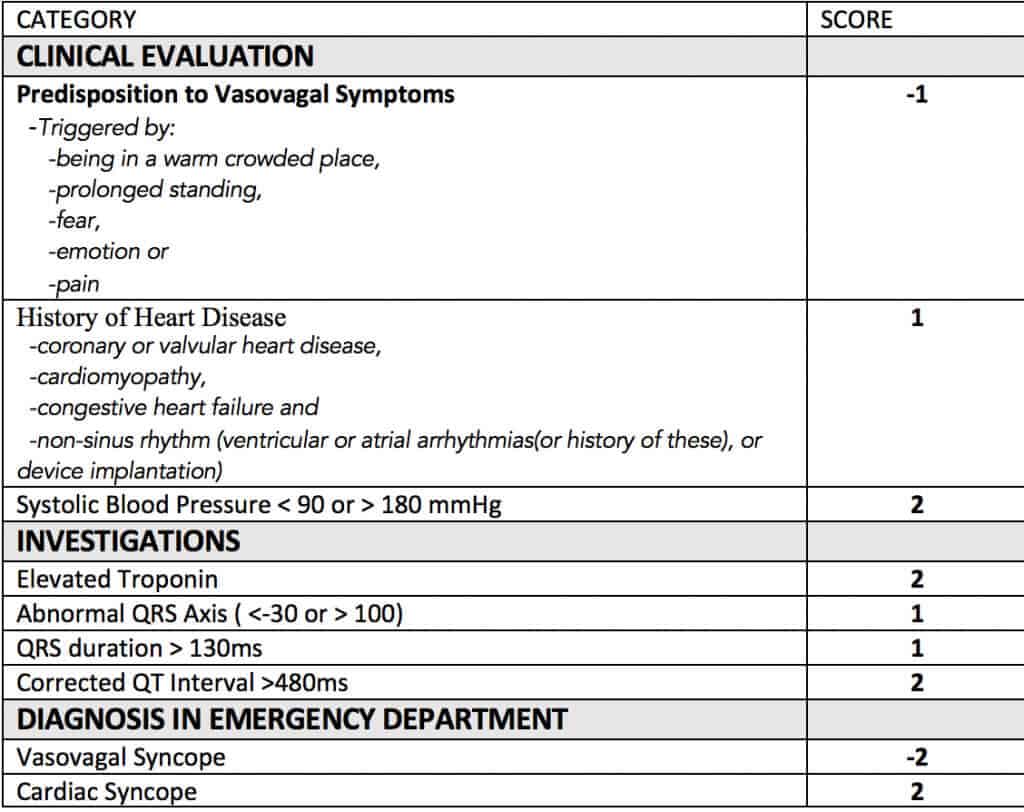

Using the data collected, 9 clinical predictors were proposed. This resulted in a scoring system that ranges from -3 to 11. The lower the score, the lower the risk.

The predictors are shown below:

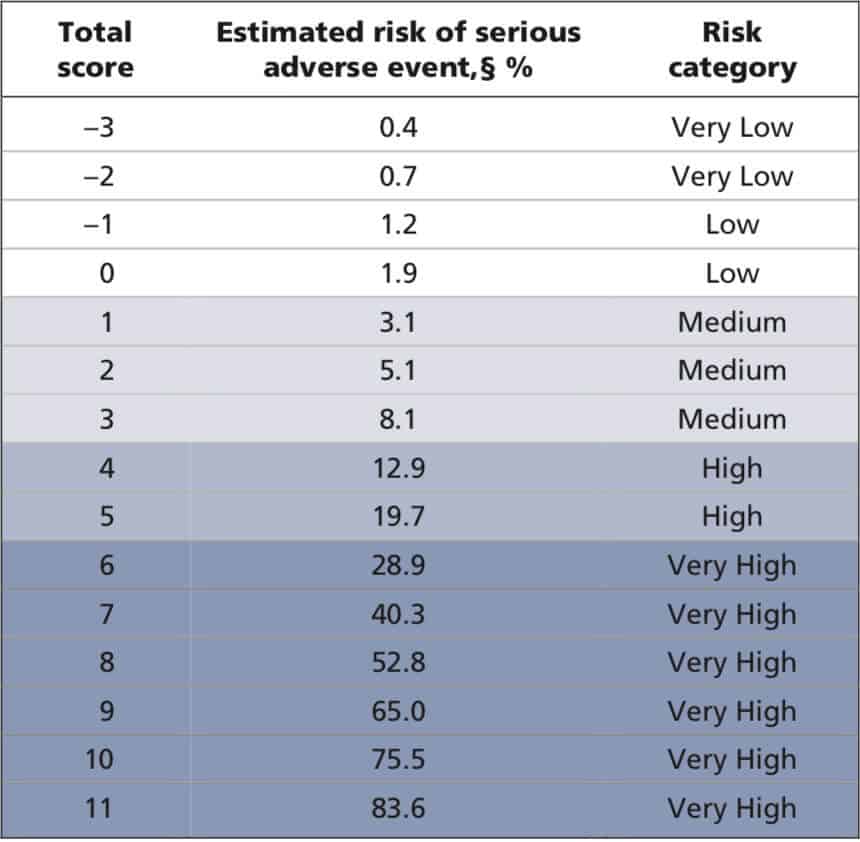

Those patient with a low risk would have a score of < 3. The risk to score, is shown below:

Limitations

There are a few limitations with this study:

- About 20% of patients that could have been recruited were not.

- Troponins were not done on every patient, and if not done, were assumed to be normal.

- A documentation of history of heart disease was missing in some patients.

- Not all patients were followed up

However the authors state, that most of the patients with the missing predictors, were in the low risk groups.

This study now needs to be validated, before we can use it.

However it is very promising.

What does this study really tell us?

It reinforces how important our basic sensible decision making is. What it really says is that in a patient that has had an episode of syncope, there is a higher risk of an adverse event:

- If your patient has a history of heart disease

- If your patient has had an episode of cardiac syncope ie no prodrome

- If your patient has abnormal vital signs

- If your patient has an elevated troponin, if it is done and

- If your patient has an abnormal ECG

This is back to good clinical medicine.